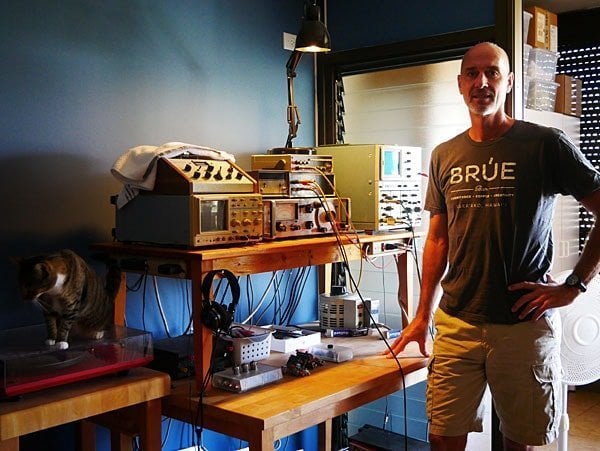

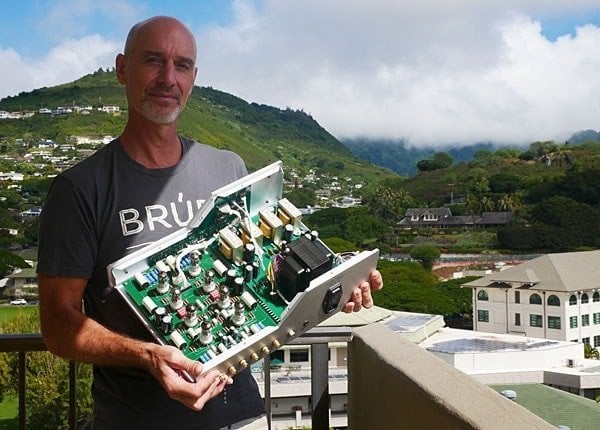

Hagerman Audio Labs is a one-man company, located in Honolulu, Hawaii, and dedicated to the design and creation of high-quality audio products. It is the brainchild and creative output of Jim Hagerman, a veteran in the analog electronics industry. Jim designs his products from scratch, ensuring that each is innovative, unique, and built to last.

Tuba Specifications

10k/50k ohm input impedance 16/32 ohm output impedance (LO/HI) 10Hz to 150kHz bandwidth (-3dB) 400mW output power @ 32 ohms 6Vrms output voltage 0.25% distortion @ 0dBV 400Hz 6 x 10 x 3.5 inches 15Vdc @ 1.35A external power supply EL84 x 2

Hagerman Audio Labs built its reputation in audiophile circles with the truly impressive Trumpet phono stage. A world class design that was a Stereophile Class A Recommended Component for years. Jim started with a clean slate and designed the chassis, circuits, and everything else.

The Tuba headphone amplifier ($670) was created from this pedigree. It’s the first headphone amplifier that Hagerman Audio has produced since 2008’s Castanet (HA-10), based on a 6H30 tube, and ‘The Ripper’ before that. Since then, Jim’s been primarily offering phono preamps, burn-in tools, guitar pedals, and guitar amps. All products are handcrafted by Jim, come with a 10-year warranty, 30-day trial period, and free shipping world-wide. Those are impressive numbers and clearly illustrate Jim’s confidence in his work. Before we take an in-depth look at the Tuba, let’s get to know the man behind the designs, Jim Hagerman.

Who is Jim Hagerman?

Jim grew up and went to college in Minnesota. He spent eight years in Boston and then went to San Diego. He worked for a number of technical companies including Digital Equipment, Hughes Aircraft, and Nokia. This is where he learned the world of analog electronics design. In the early 1990s, Jim was considering guitar amplification for his own business. He saw an opportunity in tube amplification due to many of the older technicians retiring, and few young technicians taking up the torch. Jim started reading everything available and studied for years before taking the plunge. Somewhere along the way he got diverted into phono stages and came up with the Inverse-RIAA Filter kit. He wrote a paper “On Reference RIAA Networks” for an audio publication in 1995. Around that time, Jim moved to Hawaii and created the VacuTrace, a unique piece of laboratory test equipment that converts an analog oscilloscope into a full-featured vacuum tube curve tracer. This was his stepping stone to creating the Trumpet phono stage, and as they say, the rest is history. Somewhat surprisingly, Jim doesn’t consider himself an audiophile like most of his customers. Digital Rights Management led Jim to give up on digital in 2008, and although proudly an “analog only” kind of guy (no digital sources need apply) he doesn’t have a huge vinyl collection. This design philosophy is perhaps the most interesting part of the products produced by Hagerman Audio Labs. Jim believes that topology is the key, not just the parts. He firmly believes that a better topology with inexpensive parts will outperform an existing basic design built with the most expensive components.

Tuba Aesthetics

Enter the Tuba headphone amplifier. It is the first of a new series of products built into a custom metal chassis, somewhat more upscale than previous budget units (Cornet 3, Bugle 2, Piccolo 2) in terms of appearance. The design is reminiscent of retro laboratory or industrial equipment. It’s a heavy dark grey painted aluminum case with minimal white lettering and a pointed plastic knob. The look is aggressively understated. No polished wood, no polished aluminum, and a bare minimum of switches and controls, means that the Tuba isn’t for those looking to visually impress. After reading about Jim’s design philosophy, I’m sure that doesn’t come as a surprise. While certainly not unattractive, the Tuba’s looks underwhelmed me at first. I’m unabashedly a fan of beautiful wooden enclosures and acres of polished aluminum, so a chassis that felt more like an ancient steel PC computer case, rather than a Mac, took me a while to get used to. I’m happy to report it’s grown on me. I can appreciate the no-nonsense design and focus on sound quality. As the saying goes: it’s what’s inside that counts. The Tuba is a solid machine, built to last generations, and able to compete with far more expensive units. Really, my only trifling complaint is with the ‘feel’ of the merged volume and power knob. The knob is depressed to power the Tuba on and off. The combination of the light plastic knob and the small potentiometer inside yields an impression of play (slop) and lightness. This is a departure from the weight and gravitas imparted by a solid aluminum knob that turns like syrup, usually the norm on higher-end equipment.

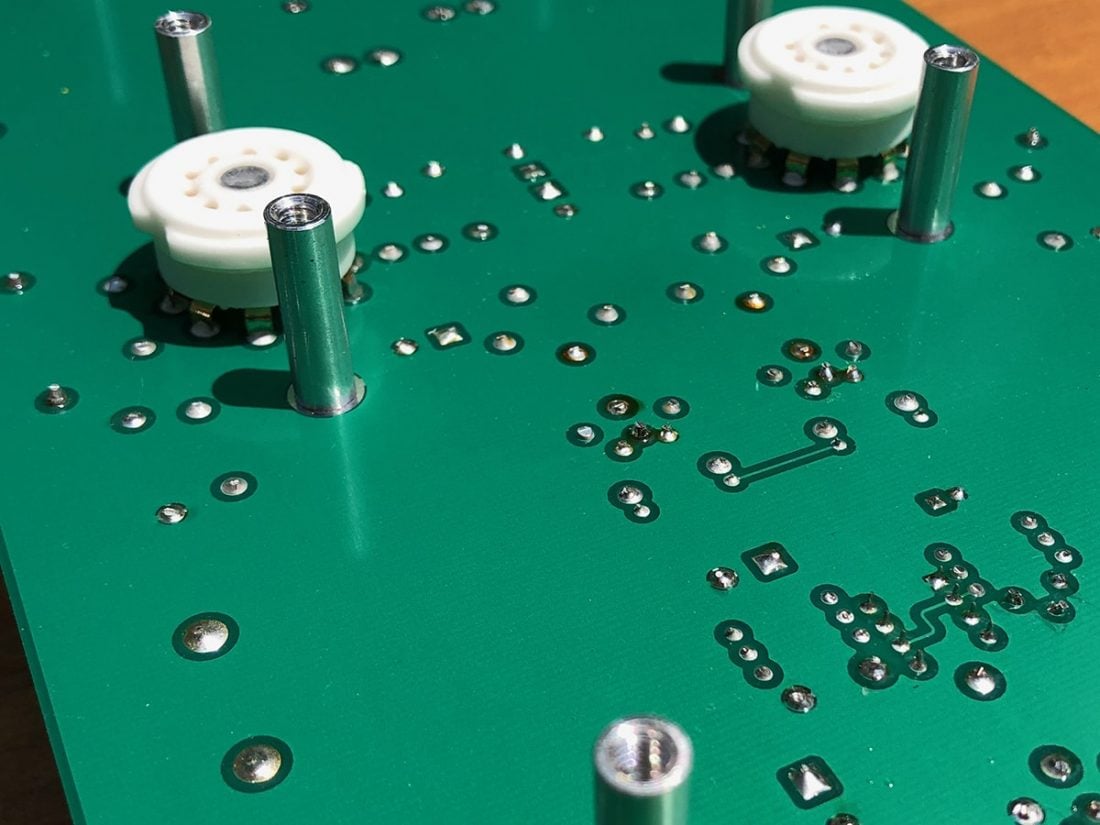

Tuba Design

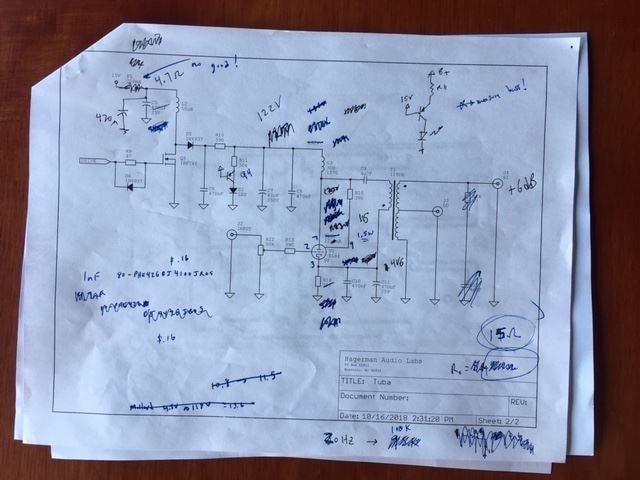

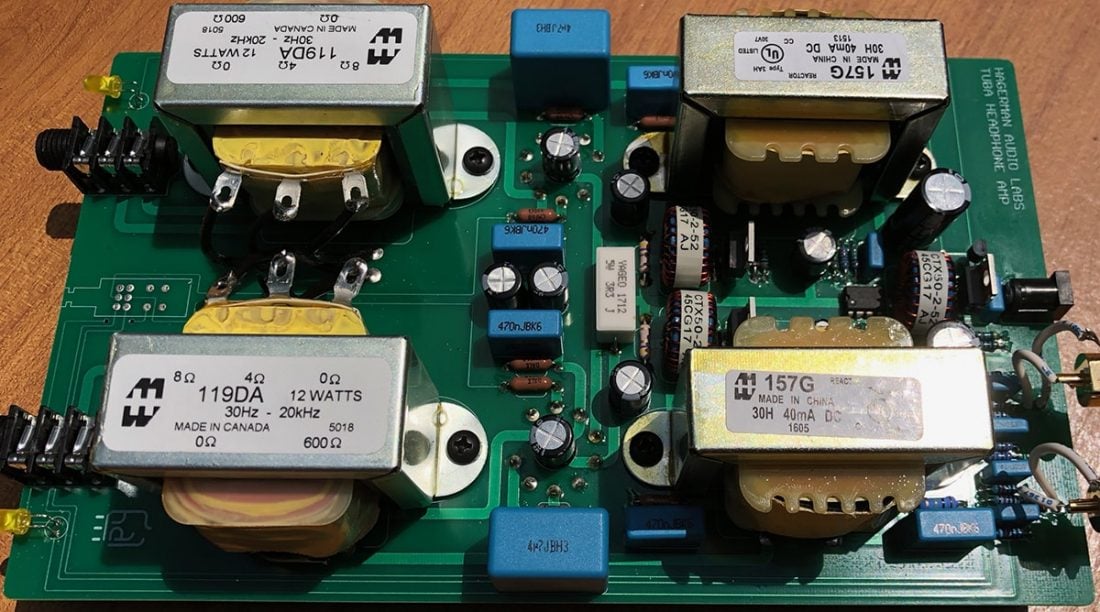

The Tuba is designed around EL84 tubes used in a single-ended, zero-feedback, parafeed triode arrangement. A matching output transformer (OPT) offers low distortion and high signal headroom, and supports high or low impedance headphones with dual outputs. Two different taps on the OPT secondary offer two output impedance levels: Jim is not a fan of output transformer-less (OTL) cathode follower circuits, as they have a trade-off between output impedance and stability. This lead to his use of an output transformer in the Tuba design. Although a transformer increases expense, Jim felt it was more than offset by a more natural and non-fatiguing sound signature. This was further enhanced with a parafeed design, where the tube is loaded by an inductor (or choke) and the output transformer is coupled to the tube with a capacitor. Removing DC current from the output transformer improves its bass response and linearity. The EL84 tube was selected with the end user in mind. The EL84 is readily available and NOS are plentiful, allowing for an easy sonic upgrade. It is worth noting that the included Mullard EL84 tubes are widely considered good sounding tubes, and are certainly far from bottom of the barrel. The EL84 tube is often described as having a tight tonal characteristic, with a strong, warm midrange focus and rich, dynamic harmonics. After a 30 second warm up delay, an internal switching power supply boosts the 15Vdc input by a factor of ten for B+. Jim implemented a special open-loop (no feedback) circuit that improves sonics, and the relatively low B+ (“only” 140V) decreases build cost and improves tube life-span. Jim views applying negative feedback as a crutch in amplifier design. Negative feedback trades gain for higher linearity (reduced distortion), but can lead to instability or more audible harshness if not properly implemented. The Tuba, although not obvious in the literature, utilizes a crossfeed circuit designed by Jim. This circuit cannot be disabled. Beyond anything else, this may impact who purchases the Tuba.

Crossfeed

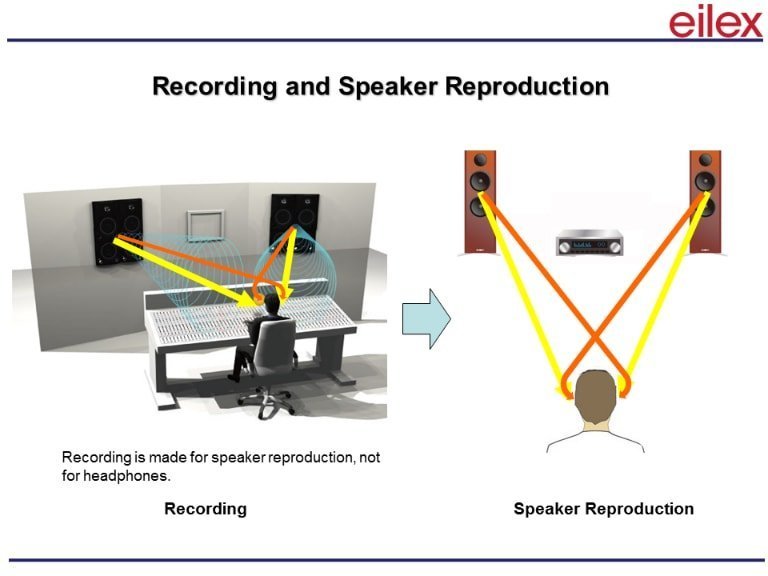

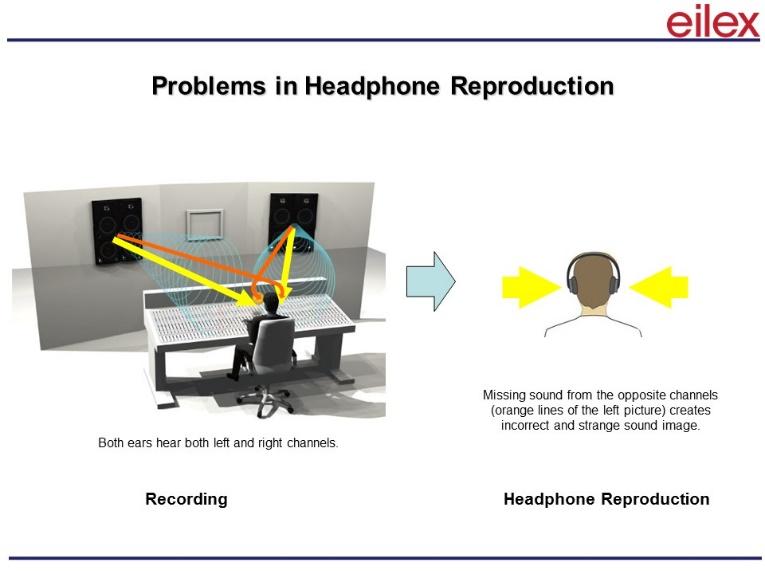

Crossfeed, like equalization, is a controversial topic for headphone enthusiasts. It tends to divide along two opposing viewpoints (seriously though, these days what doesn’t). On one hand are the Purists, who believe any fine tuning to the sound isn’t ‘how the music was intended to be heard.’ On the other hand are the Tweakers, who believe loudness buttons, equalizers, and crossfeed are viable options to improve the music they listen to. Crossfeed has to do with the differences between listening to music from speakers versus headphones. When we listen to stereo speakers, both ears hear sounds from both speakers. Music coming from the right speaker reaches the right ear, but also reaches the left ear, albeit somewhat quieter and delayed. It is this delay and attenuation that our brain uses to determine direction. In addition, reflections within the ear canal and from the environment (floor, walls, ceiling, and furniture of various shapes, materials, and sizes) further color the sound and provide more directional information to our brains. Additionally complicating things is that we don’t stay still; we continually move our heads. This non-stop movement, of course, changes angles, reflections, and the delay of the sound waves we’re hearing. None of the above apply when we listen to music through headphones. Sounds from the right driver only reach the right ear and vice versa. Without the natural hearing cues, our brain tends to interpret the music unnaturally and originating from within our head. This can cause stress and listening fatigue of different degrees for different people.

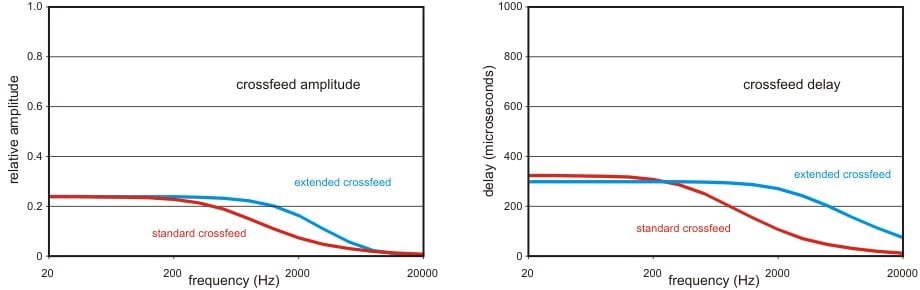

Crossfeed implementation

The purpose of crossfeed in a headphone amplifier or source is to more closely approximate the experience of stereo speaker listening. Because our brain’s ability to determine direction is somewhat frequency dependent, a crossfeed circuit should subtly mix low frequencies to both ears (less directional) while retaining high frequency separation (more directional), all the while slightly delaying the crossfeed signal to the other ear. When done properly, crossfeed can make a more cohesive soundstage and reduce listening fatigue. The end result should provide a more natural and realistic sound and listening experience, and not be an overt gimmick.

The crossfeed argument

Anti-crossfeed purists will often report that they find crossfeed blurs the music, making it less defined, with less focus, and a lack of desired crispness. Of course, whether you like crossfeed or not has much to do with your personal listening preferences and expectations, as well as how the circuit is executed. Some implementations sound better than others.

Purist viewpoint

That’s the way the music was recorded and intended to be heard. Crossfeed is inaccurate and alters the history of the music. A good recording has microphone placement to represent the soundstage and proper reproduction without crossfeed duplicates this soundstage. Crossfeed blurs the sounds across the soundstage and muddies the stereo image. Crossfeed meshes instruments together so that separation and details are lost.

Tweaker viewpoint

Most music is stereophonic and not made or mixed for headphones. Crossfeed makes stereo recordings more accurate for headphones. What good is ‘pure sound’ if it fatigues or bothers the listener? It is unnatural for the brain to hear sounds through just one ear.

Testing crossfeed

The effectiveness of crossfeed has much to do with the type of music you are listening to. Older recordings (often of the classic rock variety) sometimes used very separated channels within songs. Extreme examples placed vocals on one side and guitars or drums in the other with little to no bleed over. Technological advancement in recording and playback moved music from predominantly mono to stereo through the 1960s. This led to much experimentation and some extreme examples of stereo panning in recordings of the time. Albums originally released in mono (such as the Beatles’ early albums) were occasionally re-released in the new ‘stereophonic’ format. While this practice was more commonly found in 60s rock, some feel that the large orchestral or choral music benefits from crossfeed the most. Extremely wide stereo separation seems to be less common within modern recordings. Crossfeed is much less noticeable with recordings that are equally balanced between both channels. However, crossfeed implementation should still benefit the headphone listener with improved spatial cues and reduced listener fatigue regardless of the recording.

Music to test crossfeed

Elanor Rigby – The Beatles The Doors (self-titled album) – The Doors You Lost that Loving Feeling – The Righteous Brothers The Sound of Silence – Simon and Garfunkel

Crossfeed in the Tuba

The crossfeed circuit in the Tuba is very, very subtle. Honestly, if Jim didn’t tell me, I sincerely doubt that I would have noticed it on my own. To test, I simultaneously connected the Tuba and a Bottlehead Crack (no crossfeed) and played the music tracks above. Switching back and forth quickly between them, I compared the hard panned sections of the songs. Eventually, I ended up plugging one ear and listening solely through the other to distinguish the difference in sound. Like I said, subtle. Don’t let the fact that you can’t disable crossfeed talk you out of this amplifier.

Tuba Sound

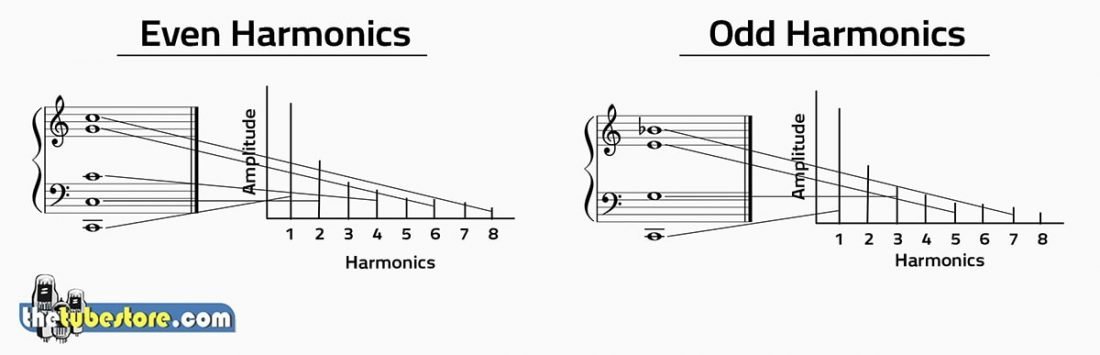

As expected, the Tuba is a very well-mannered and non-fatiguing amp to listen to. If you are familiar with triode tube amplification, the Tuba displays the expected warmth of sound. This warmth is primarily due to harmonics or overtones, the sounds between the notes. Although all amplifying devices create harmonic distortion, tubes, especially when used in single-ended amplification, produce a harmonic profile that many consider pleasant. Tube amps are not theoretically “ideal” amplifiers that simply apply voltage gain. With a tube amplifier, it is important to understand that harmonic distortion is often part of the intended sound signature. Harmonic distortion may be defined as the presence of frequencies in the output signal that are not present in the input signal. These frequencies may be even or odd and high or low. Second order (low-level, even) harmonics are often considered “what you want with a tube amplifier”. They tend to add a pleasant sounding, organic warmth to the sound. Throughout my time with the Tuba, I found it to be very laid back and non-aggressive. It’s an easy amp to like and to listen to for extended periods.

Tuba Power

The Tuba’s relatively low power reinforces the impression of refinement and quality over quantity. This is a bit of a concern as headphone pairing becomes important. I’m used to OTL tube amps that require high-impedance headphones only, so I was excited to spend time with a tube amplifier that should be less picky about headphone pairings. Sure enough, the Tuba sounds great with very sensitive in-ear monitors (IEMs) like the KZ ZS10 Pro. It has a very low noise floor and doesn’t add any unwanted hiss to playback, something I can’t say about most of the other desktop amps that I use. It’s the other end of the spectrum that is more of an issue. Jim mainly used the Sennheiser HD600 and Grado SR125 for development, two very different headphone types with contrasting loading characteristics. So I tried my own HD650 and SR325 headphones (SR325 using the Low output and HD650 using the High output). I can happily report that the Grado SR325 has never sounded better with any other amplifier I’ve tried. The laid-back sound of the amp paired with the brighter Grado signature is a terrific combo. It made me remember why I fell in love with the Grado house sound the first time. The HD650 also worked well. However, normal listening levels require about ½ on the volume knob. Cranking up to ⅔ or ¾ is necessary if you really want to boogie (I’d forgotten how good that first Digital Underground album really is). By contrast, my modified Bottlehead Crack requires ⅓ – ½ of its useable range to achieve the same volume. The Crack, shod with Tung-Sol tubes, also sounds more alive and engaging through the Sennheisers. Admittedly the HD650 and Crack pairing is the very definition of synergy, and seems to bring out the best in both partners. The 600-Ohm Beyerdynamic T1 are just that much harder for the Tuba to drive. Adequate volume can be achieved, however it requires most of the volume control. How about the planar Fostex T50RP mk 3 (and Alpha Dog variant)? Fuhgeddaboudit. There just isn’t enough power on hand to drive them properly. So take a look at your headphone collection before you consider a Tuba. IEMs and efficient full-size cans? Absolutely. Inefficient planar magnetic monsters? Not so much.

Conclusion

Jim Hagerman at Hagerman Audio Labs is an easy man to respect. He brings an old fashioned sense of innovation to design, construction, and sales that appear focussed on quality rather than profit. Jim found his love of music reproduction early–reportedly at 16 with Klipschorns and Supertramp’s Crime of the Century–and throughout his career, he has genuinely added to the pursuit of high-end audio. Jim started by offering kits to enthusiasts, and still is one of the few to publish his schematics online. This illustrates his commitment, pride, and confidence in his designs, even though it opens him up to intellectual property theft and cheap knock-offs. The Tuba is Hagerman Audio Lab’s first headphone amplifier (in ten years) and it introduces Jim to a brand new group of audiophiles. These days, it seems the majority of headphone users have moved on to digital sources and, as such, may not be aware of Jim’s lengthy expertise in analog audio reproduction. It’s really nice to know that there are still pros like him producing new designs. The Tuba is a unique product. It really doesn’t remind me of anything else currently available. The combination of tube warmth, polite sound, highly-efficient headphone compatibility, and crossfeed will make it ideal for some, but not for all. It certainly brings something different to the table for someone who currently owns an OTL tube amplifier. Like its namesake, the Tuba is not a jack of all trades. However, if the no-nonsense design appeals to you, and if your headphone collection is a good match, it is well worth the audition. Remember that free shipping, a 30-day trial period, and a 10-year warranty means you have little to lose. You might just find exactly what you are looking for.